Serving the Vermont Champlain Valley Area for 45 Years

Main SectionsFront Page SportsValley VitalsIt's in the StarsStarwiseArchivesLinksAbout The VoiceContact Us |

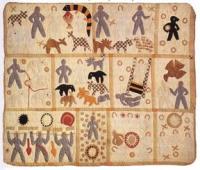

Stitched Into Freedom: The Role Of Quilts In The Underground RailroadTuesday June 7, 2011 By Cookie Steponaitis In hope chests and places of honor around the nation are heirloom quilts that were lovingly stitched and passed down through generations. Some are records of a family tree and others are collections of fabrics and images that carry great personal meaning. Still more occupy a distinct place in the history of this nation, for they were a part of the Underground Railroad that was hidden in plain sight and had roadmaps and itineraries for runaway slaves as they struck out for freedom in the north. Quilter and historian Jacqueline Tobin grew up hearing stories of local families’ roles in the Underground Railroad. In particular she sought to tell the tale of Ozella McDaniel Williams from South Carolina who told tales of using the patterns of quilting as a code that was stitched into specific quilts and left to hang at the plantation as a guide. Fifteen distinct patterns formed a primitive Morse Code that was translated by those who could read for those who could not. The quilts ranged in complexity from basic stitches to works of art and were used as a communication tactic by the Underground Railroad and its precious cargo of runaway slaves from as early as 1845 on. Ms. Tobin asks Ozella in her book Hidden in Plain View for a translation for one specific quilt and with her words the quilt takes on a new life and role as a road map. “The monkey wrench turns the wagon wheel toward Canada on a bear’s paw to the crossroads. Once they got to the crossroads, they dug a log cabin on the ground. Shoofly told them to dress in cotton and satin bows, go to the cathedral church, get married and exchange double wedding rings. Flying geese stay on the drunkard’s path and follow the stars north.” Realizing that the role of slave labor in the production of textile products was not only encouraged in the south and not seen as any kind of threat, organizers of the Underground Railroad incorporated putting quilts out to air on the fences as a way of having slaves communicate with each other and quickly came up with codes for different quilt patterns and the sequences in which they were used. The quilting was also a way for slaves being allowed to gather and share ideas. These quilting groups are documented throughout the south, but to date no formal study has been undertaken to determine how the networks became connected and the first links with the Underground Railroad movement were created. The slaves often used these gatherings as a way of seeking emotional support while they were denied the right to read and write. Quilts became replacements for diaries and often recounted key events in the lives of slaves and their families. Made up of squares that the slaves referred to as “memory patches,” each quilt became an expression of art, protest, and even hope. The quilts are just beginning to be appreciated and preserved as an art form. Mentioned in southern travel accounts, plantations records memoirs and diaries of whites and slaves, quilts were a traditional female trade and taught the slaves skills that allowed them to expand their use of the traditional arts to create something uniquely their own. While “women’s work,” these quilts became reflections of the religion, hardship, tenacity and spirit of over one hundred years of slaves. While history argues about the beginnings of the phrase “Underground Railroad,” most speculate that its origins began around 1831 by a fugitive slave named Tice Davids who had escaped in Kentucky and was in northern Ohio. His owner searched for months for the slave and was reported to have commented that, “The nigger must have gone of on some underground railroad.” However it first came into use, by 1840 the name and the practice of moving runaways from southern plantations to the relative freedom of the north or ultimate freedom in Canada was an established practice. Quilts were used as bed coverings, pallets on the floor, baptismal ceremonies, and substitutes for ironing boards, cushions for wagon seats and as a carrying device for children, serving a multitude of uses in daily life. Made mostly of discarded goods or thrown away items, slaves carded and pieced together leftover pieces of raw cotton, wool and other fabrics to create a wonderful array of pieces. One ex-slave even recollected of her own escape, “ One day mammy come afte’ me an I run an hid under a pile of quilts an’ laked to smothered do death wittin’ for her to go and take us all off.” While historians may still continue to debate the amount of evidence supporting the premise of quilts serving as coded messages and road maps, all involved in the studies are certain of one thing. Stitched from the hearts and souls of American slaves, the quilts are masterpieces of art and a source of history hardly ever studied or examined. They remind us of an art form still honored and kept alive in the hills of the Green Mountain State that offers a unique window into a time in American history where few publicly spoke of dreams of freedom for fear of reprisal, but chronicled the struggles of a people and the hopes of a better future in cloth for all to see.

|

AdvertisementsSearch our Archives |

Agricultural Weather Forecast:

© 2006-18 The Valley Voice • 656 Exchange St., Middlebury, VT 05753 • 802-388-6366 • 802-388-6368 (fax)

Valleywides: [email protected] • Classifieds: [email protected] • Info: [email protected]

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly